Hi Beautiful Friends,

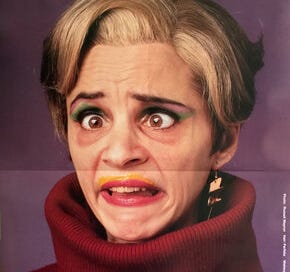

This poster was not part of Wyeth/Pfizer’s marketing campaign for Premarin. Leave it to Amy Sedaris to pull off humour while simultaneously bringing light to a dark issue. In Part I,

we covered the ups and downs of estrogen from its discovery to its extraction from pregnant horses.

Now let’s take a look at Premarin’s elaborate and novel marketing campaign that overcame cancer and limited data to reach sales of over $2 billion in 2001 only to be crushed by the WHI in 2002.

It’s important to understand how culture in the 21st century impacted public and medical perception of the hormone estrogen. First, it was raised up onto a pedestal as a cure-all elixir of never-ending youth. With that impossible expectation, estrogen was doomed inevitably to fall. The crash was heard worldwide.

Freud on Menopause

I loved reading Freud in college. I used his theories to analyze and write papers on the origin of my night terrors as a child. His ideas struck me as brilliantly intuitive. They helped me deepen my understanding of myself and human behaviour, and sparked a lifelong curiosity in psychology. Vestiges of id, ego, and superego undergird modern talk therapy approaches of today.

Freud made many remarkable insights; he also made many mistakes, especially about women, setting the stage for misinterpretations and mistreatment. Freud described menopause as “a crisis period during which a woman mourned the end of her feminine attractiveness and child bearing capacity.” He stated that “It is a well-known fact” (the classic non-evidence-based frame of conventional medical “wisdom”) “… that after women have lost their genital function their character often undergoes a peculiar alteration.” They become “quarrelsome, vexatious and overbearing.” Sounds to me like he’s describing perimenopausal rage. Some women may appear that way, as I have in moments when I’m at my limit, overcome by the necessity to express valid frustrations under immense emotional load after a night of disrupted sleep.

In contrast, two OG women’s rights activists had a different view of menopause. In an 1857 letter, Cady Stanton wrote to her friend Susan B. Anthony, “We shall not be in our prime before fifty & after that we shall be good for twenty years at least.” In fact, both suffragists enjoyed the benefits of menopause (they do exist!) for them to continue their life-changing activism.

Freud’s excoriating and depressing perspective shaped public opinion. His remarks told women how they would feel about this inevitable transition and how people would feel about them as they moved beyond reproductive years. The advertising for Premarin is chalk full of images and messages that reflect the same abysmal perspective.

Mad Men’s Menopause

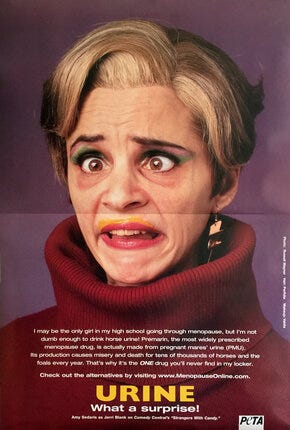

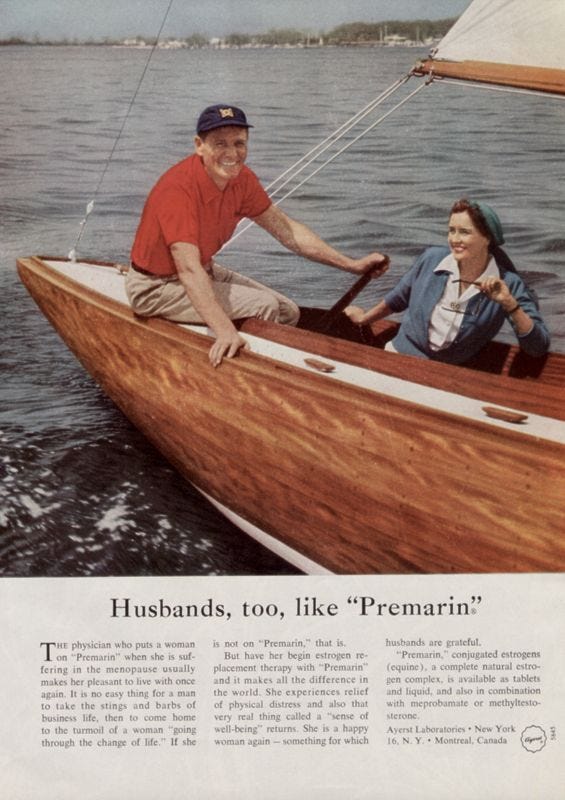

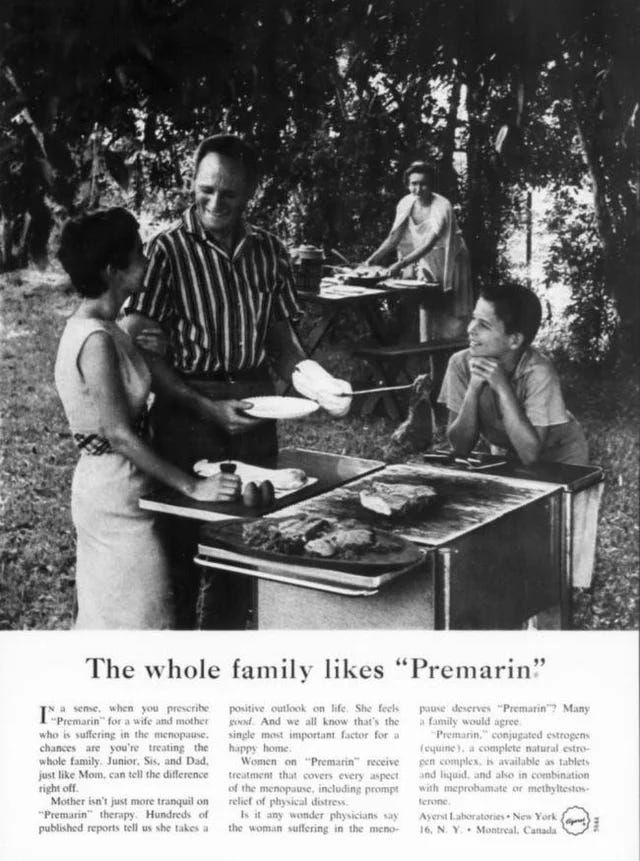

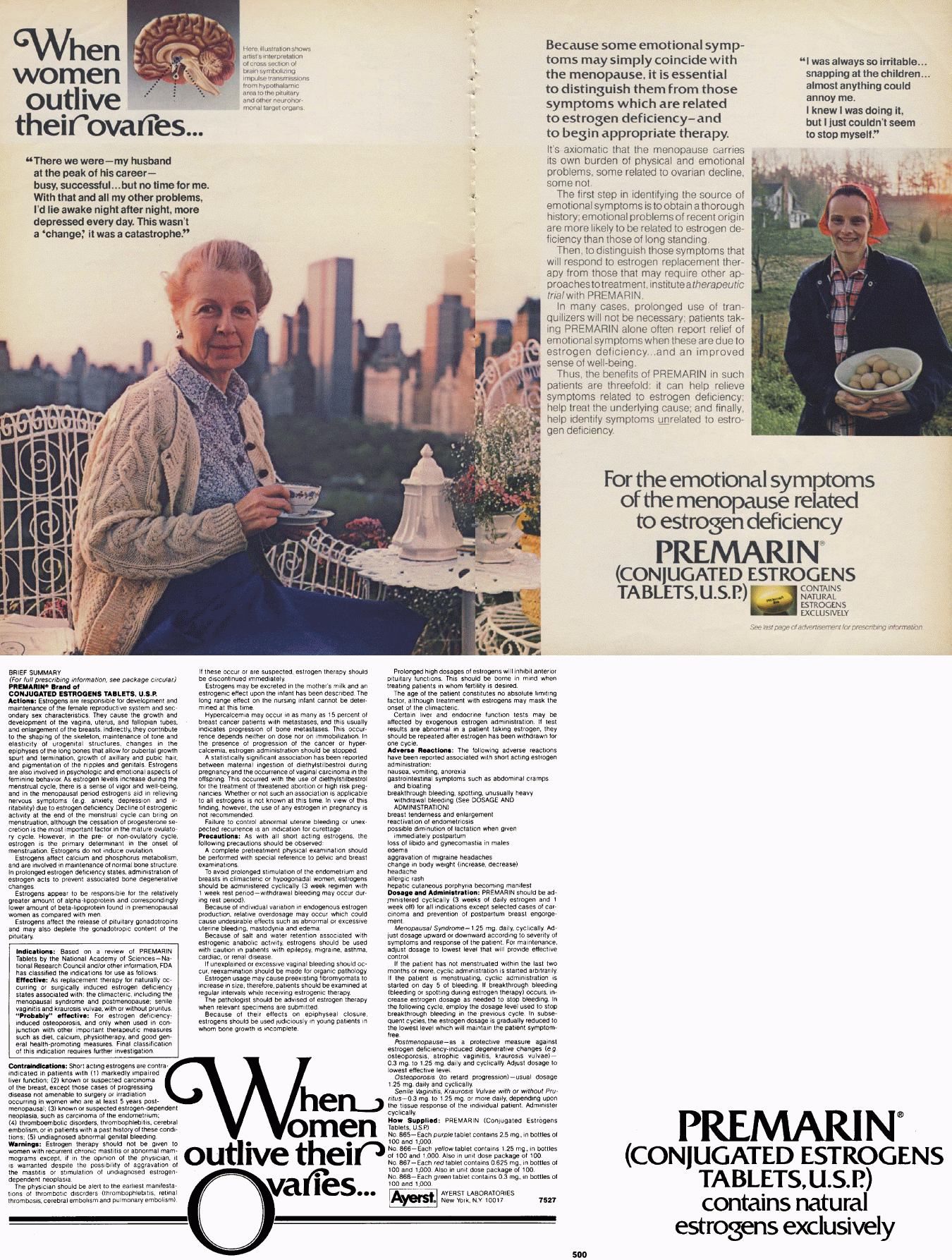

Here are some ads for Premarin that appeared in popular print publications from the 1950s to 1970s.

The objectification of the woman in the ad directly above invokes the male gaze, appealing to the desire to keep a woman young and pleasing to the eye as well as pleasing in temperament. The appeal has little to do with a woman’s internal sense of wellness. Rather, it encourages her to chase an impossible goal of eternal youth for the sake of maintaining attractiveness to the men around her.

Here’s what the text from the ad above says:

“…when you prescribe “Premarin” for a wife and mother…chances are you’re treating the whole family. Junior, Sis, and Dad, just like Mom, can tell the difference right off. Mother isn’t just tranquil on “Premarin” therapy. Hundreds of published reports tell us she takes a positive outlook on life. She feels good. And we all know that’s the single most important factor for a happy home.”

In all of these ads, the benefits of Premarin are viewed predominantly from the perspective of those in relationship to the wife or mother, (or unhinged woman on a bus, who I personally think looks kinda fun).

Mother’s Little Helper

Notice the word “tranquil.” From the 1940s to the 1980s, tranquilizers were a common prescription for women suffering emotional disturbances such as depression and anxiety, common symptoms of estrogen decline during perimenopause, and certainly made worse by restrictive roles with perfectionist expectations. Valium was the first $100 million drug brand in America and became as common as razors and toothbrushes in the family medicine cabinet according to Andrea Tone, author of The Age of Anxiety: A History of America’s Turbulent Affair with Tranquilizers. This very addictive benzodiazepene, eventually classified as a Schedule IV drug, was coined “Mother’s Little Helper” in a song by The Rolling Stones in 1966, the same year Dr. Robert Wilson would publish Feminine Forever, the best seller considered largely responsible for Premarin’s marketing success. Feminine Forever would make Premarin a competitive alternative for improving mood over benzos. Dr. Wilson would repeat Freud’s negative menopause messaging bolstered by Premarin ads that reinforced Wilson’s hyperbolic claim that “No woman can be sure of escaping the horror of this living decay.”

Building an Empire

As seen in the awful story of oxycodone, the first step for a drug company in building an empire is to identify a disease or health problem. The next step is to develop a drug to treat the problem. The final step is to find doctors to sell the cure. Together, Wyeth and Dr. Wilson did just that by first labeling menopause, right on the cover of his book, as a “hormone deficiency disease.” His fear-mongering language opined the “galloping catastrophe” of menopause after which all women become “castrates.” Dr. Wilson was Wyeth’s first soldier in the battle to make Premarin a panacea for all aging of all women, selling it for protective benefits yet unproven.

Ghostwriting also played a role in the Premarin campaign. In one of the many breast cancer lawsuits that happened after 2002, Wyeth was forced to unseal documents that illuminated the building of the Premarin empire. On one of the 101 pages released, in hand-written notes, are the words “dismiss/distract,” a common strategy for companies when faced with a possible risk associated with a profitable drug. A company called DesignWrite was responsible for drafting abstracts and articles for medical journals and then had doctors sign off as the authors to give the pieces credibility. Doctors, highly influenced by what they read in respected medical publications, then became the army following Wilson into the battle to cure the disease called menopause.

The Fever of Feminine Forever

From the 1950s to the 1970s, estrogen therapy tripled. Dr. Wilson sold women (and their husbands) on the excitement of averting the process of aging by writing claims such as:

“Breasts and genital organs will not shrivel. She will be much more pleasant to live with and will not become dull and unattractive...At fifty, such women still look attractive in tennis shorts or sleeveless dresses."

If that quotation put a bad taste in your mouth then you probably won’t be surprised by what came next…

Feminist Backlash

Feminists were split on Wilson’s book, seeing hormone therapy as anti-feminist in one camp and pro-feminist in the other.

Our Bodies, Ourselves, published in 1970, pushed women to learn more about their bodies and take control of their medical care from an informed position.

The British journalist Wendy Cooper wrote Don’t Change: A Biological Revolution for Women, which touted hormone therapy as an aid to support vitality through the challenges of hormonal transition.

On the other hand, many disliked Wilson’s suggestion that menopause was a disease to be treated and even cured (a biological impossibility) rather than a “natural” transition. He went so far as to liken menopause to diabetes since both, he claimed, could be cured with the addition of a missing hormone, estrogen in the case of menopause and insulin in the case of diabetes. (The Hormone Decision, p. 65.) Two other books, Women and the Crisis in Sex Hormones by Barbara Seaman, and Menopause: A Positive Approach by New York Radial Feminist member Rosetta Reitz, both argued against the gender-biased ideas of keeping a woman youthful and tranquil. They criticized the medicalization and pharmaceutical stance. Firmly anti-estrogen, they urged women to take an empowered and “natural” approach. (Estrogen Matters, p.61)

Some of you may already know how I feel about the word “natural” in the context of many things but particularly, menopause, which I wrote about in this post:

Here’s the thing. We might argue that using hormones for better quality of life, among other demonstrated protective benefits, is no less natural than using birth control to prevent pregnancy or fertility treatments to conceive. We also enjoy the choice of an epidural during labour to manage pain, not to mention many modern technologies that help us control our bodies. “So why do the rules about medical technology suddenly change once a woman hits menopause?” (The Hormone Decision, p. 51). I’m with Tara Parker-Pope. This is just the tip of the rabbit hole, to mix metaphors, but I’m going to step over it. I just needed to share what a challenge it is for me every time the word “natural” comes up, which is frequently in the conversation around menopause.

Starting the Conversation

While distasteful in oh so many ways, Wilson’s book was at least finally bringing much needed attention to the lack of care women faced during hormonal decline. Rather than being dismissive, here was someone who recognized that with the help of estrogen women might suffer less. Unfortunately, we also had to suffer his patriarchal and sexist views. Women were rightly repulsed by his focus on traits of “femininity” a woman should strive to maintain in order to stay attractive and useful to her husband. Barf.

The problem, similar to what we see in the ads above, is that Wilson focused on the benefit to husband by keeping her youthful and attractive, and to family by keeping her cheerful in the role of subservience to all other members of the family. Instead, the feminist argument in favour of hormone therapy acknowledges the possible benefits of estrogen to improve quality of life not just for her family but for herself, to give her back control of her own body, and to support her continued drive toward pursuits professional and otherwise.

Marketing responded to the women’s movement and began focusing more on practical guidelines determined by symptomatology and science. It also began targeting older women, which the WHI demonstrated is not the safest age group to receive hormone therapy, especially when initiating treatment 10 years post menopause. Notice also the dropping of the word “equine.”

As time progressed, Wyeth’s marketing campaign became more sophisticated as we see in this television ad in 2000 featuring the well-known actress Lauren Hutton. Premarin isn’t mentioned at all. Instead the actress describes the symptoms of estrogen deficiency and the various chronic health issues related to aging that may be helped with hormone therapy. She encourages women to speak to their doctors to protect their health with no emphasis on maintaining youth. Looking straight into the camera (a technique we’ll see again with Suzanne Somers), she urges “Believe me. The time to protect your future is now.”

In the end, the Women’s Rights Movement agreed upon one thing: the need for more and better research. Seaman adovcated for the National Women’s Health Network in 1975, which demanded more rigorous studies. (The Hormone Decision, p. 69)

In Part II (b) we’ll take a look at studies through the 80s and 90s that set the controversial stage for the WHI and likely impacted the flawed design that destroyed estrogen’s reputation, leaving it out in the cold despite many promising results.

In Solidarity

The Premarin ads are outrageous! Except for the one from Amy Sedaris, hard not to smile at that one. It's sad to think that our mothers experienced such distorted messaging, and that the only way they could find happiness was by trying to live up to an impossible stereotype by ingesting horse urine.