Hi Beautiful Friends,

While the ad at the end of my last post:

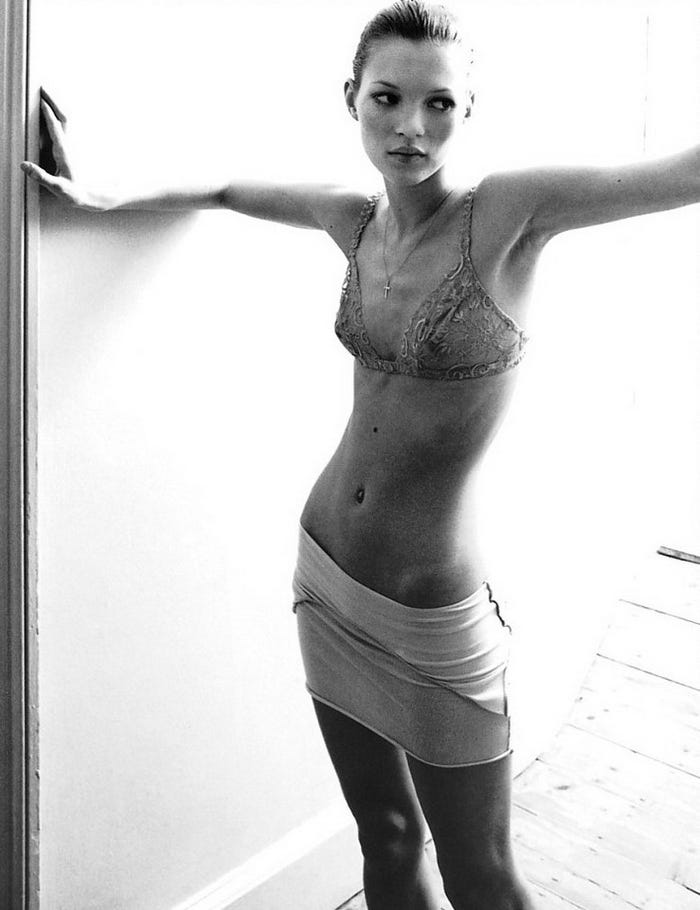

may have turned your stomach, the ideal female shape as promoted by media went from bad to way worse. In the 1980s we witnessed the birth of the supermodel. And if that ideal of thinness wasn’t extreme enough, the 1990s brought us heroin chic epitomized by model Kate Moss. In a 2009 interview, she didn’t coin the phrase but shared “nothing tastes as good as skinny feels” as the mantra that had kept her skeletal for photo shoots.

I think most of us today recognize the cultural illness inherent in the idealization of this image of emaciation. The use of light and shadow further accentuates her thinness to create the illusion of a woman vanishing in front of our eyes, a disappearing act that became reality for some.

In 2006, Luisel Ramos Arregui, on her way back to the dressing room after walking the runway during Fashion Week in Montevideo, Uruguay, dropped dead of a heart attack induced by anorexia. At 5’9” she weighed 96.8 pounds. The modeling world responded by banning models with a BMI less than 18, although 18.5 is considered the bottom range of healthy. The move toward slightly larger models happened too late for Luisel’s younger sister, also a model, who died a year later of the same cause. Anorexia is often a progressive disease with about a 50% total cure rate over the lifetime and a 70% rate of relapse.

When the Call Comes from Inside the House

Into old age, my grandmother was always very proud of the fact that she had maintained the same body weight since the age of seventeen. She died two weeks before her ninety-third birthday, thin and frail with barely a hair on her head. A wig covered the baldness but couldn’t hide the deterioration of the once brilliant mind underneath it.

While her waist circumference may not have grown over the decades, the long list of foods she was “allergic” to surely had. I often wonder if her eventual demise was caused, or at least made worse, by malnutrition. She managed to stay alive a long time, but her health in the final years declined considerably, preventing her from enjoying all the lifespan she was given. The premium she placed on remaining flat-stomached may have impacted her healthspan; it certainly impacted her daughters’ and granddaughters’ self-perceptions, body dissatisfaction, and eating habits.

I remember how hard my mother laughed when I shared a line from a play I read in college. In a one-woman show written for Lily Tomlin, a character named Chrissy, huffing away in an aerobics class, bemoans that she’s lost and gained the same ten pounds so many times her “cellulite has déja vu.”

My mother could relate. She lived in the hamster wheel of fad diets. Those diets changed depending on which book she was reading - from Atkins, to eat right for your blood type, to the Zone. While the diets changed, the self-criticism of her size and weight remained, along with the constant battle to become smaller than her body wanted to be.

Her eating style consisted of cycles of restriction and bingeing. Sometimes restriction was sustained over several weeks if she was dieting to fit into a dress for a special occasion or a bathing suit for an upcoming tropical vacation. While on holiday, she entered the indulge phase accompanied by her habitual, audible oaths that her diet would begin again as soon as she got home. In her daily routine, she’d often go all day seeing patients on little to no food and then eat a large dinner. She kept some stale jujubes in the car that she’d snack on when blood sugar would get low while driving between home, her office, and the hospital. For the record, while my mother stayed chained to the diet treadmill, she was never “obese,” a word I’ll get to in a bit.

Invisibility of Eating Disorders

While the link between bodybuilding, or modeling and anorexia is more visible, bodies of all shapes and sizes can suffer from eating disorders. Just imagine seeking help for mental illness and disordered eating that is jeopardizing your health, only to be disbelieved, or even laughed at, because you don’t inhabit the stereotypical body that people and medical professionals associate with the disease. Imagine how it must feel for someone brave enough to speak up about their internal experience of body image disturbance that fuels their disordered eating, only to be told that they couldn’t possibly be sick because they don’t look that skinny. When someone struggling with disordered eating hears that she isn’t thin enough to be anorexic this message can further fuel the disease just as praise for a thin appearance can perpetuate eating too little to maintain that look.

Commenting on the physical appearance of women and girls is an accepted and deeply ingrained social behaviour. It gives us something to say when we’re at a loss. Although the intention may be kind, even our compliments reinforce that our value is in our outward appearance rather than our internal experience.

These two things can be at extreme odds for people with body image disturbance. Positive remarks from others are often disbelieved by someone suffering from body dysmorphia whose image in reflection shifts from day to day and sometimes even from morning to night. When the mind plays these tricks, the mirror becomes a fun house experience of distortion, only there’s nothing fun about it.

Origins of Body Image

For women, few self-descriptors are as abhorred as the word “obese,” so shrouded in stigma that there’s talk in the medical field of replacing it with Adiposity-Based Chronic Disease. Some may roll their eyes at this analytic mouthful of a term, but the truth stated in Exacting Beauty, a comprehensive, clinical text on body image disturbance, is that “body size remains one of the few personal attributes (vs. ethnicity or disability) that many individuals still see as an acceptable target of prejudice.” Granted, that book was published at the beginning of this century, so we’ve likely (or hopefully?) made some progress, but I’ll leave that to the in-group to decide. Regardless, most people my age probably remember growing up at a time when fat jokes were frequent. And teasing is a strong modifier of behaviour.

Interestingly, not every young girl will be as susceptible to the thinness ideal. The American Psychological Association states that mere awareness of the underweight ideal does not correlate to body image disturbance as much as other sociocultural factors. A stronger factor for eating disorder symptomatology is whether someone has internalized the ideal of thinness as her own. Reinforcement, through teasing, punishment, negative commenting, and even praise from family and peers strengthens internalization.

Data reveals that the goal to lose weight often begins around puberty (younger in some cases), may diminish slightly through the twenties and thirties - often the reproductive years when women accept bodily changes without as much self-judgment - and then hits another peak during midlife. Some weight gain through midlife has no bearing on health and may even provide some protection. For others, weight gain impacts health. The problem is that most current means to address weight gain and provide weight management are failing miserably. You’d be hard pressed to find a business platform better than the weight loss industry at raking in cash in spite of failing to provide long-term, sustainable results for its customers. Well, maybe a Las Vegas casino.

Diet Cycling

“Although weight loss and regain may seem harmless, it’s not. In addition to the psychological toll (frustration, distress, shame, and guilt), there is a physiological impact on bone, muscle, cardiovascular health, and cancer risk with weight cycling (repetitively losing and gaining weight).”

Val Schonberg explains the consequences of diet cycling as something she experienced in her own body and has seen in her clinical practice of over twenty years. She believes that our bodies are smart. Cycles of restrictive eating can cause the body to hold on to stores in preparation for the next self-induced famine, especially when that happens during midlife amidst fluctuating hormones. This pattern of yo-yo dieting over the years plays a much greater role in weight gain than the often blamed, alleged slowing metabolism. The body tends to respond to sudden, extreme changes in eating with initial weight loss, but rarely do severe diets provide sustainable habits. Bodies tend to regain weight over the long haul.

It’s not your metabolism

A 2021 large study contradicts the common belief that our metabolism slows down through the menopause transition. Measurements from close to thirty different countries in over six thousand people aged eight to ninety-five showed that total energy expenditure and lean tissue remained stable between the age of twenty all the way up to sixty. Energy expenditure declined only after age sixty, at which point both fat and lean tissue decreased during this later stage of life.

Skinny Privilege

I swear my sister could have been an Olympian. She was born with natural physical abilities and coordination absent from my chromosomes. However, unlike my sister, who is six feet tall (and has been since about age twelve) and strong as an ox, I avoided certain bodily scrutiny and teasing from family and skating coaches by being thinner. She always carried more body fat but, correspondingly, more muscle and strength, and, consequently more power.

Although my sister three years my junior and I, spent the same number of hours at the rink, I struggled to keep up with her. Test days were torture. I’d pray to get a “pass” on the slip of paper handed over by the panel of cold, grumpy judges whose job was to find any imperfection inevitably exposed by my wobbly, freezing bones fighting to stay upright. If I was lucky enough to succeed it just meant on to the next one in an endless series of tests recognizing levels of achievement (and thereby, worth within our skating and achievement-obsessed family).

I remember watching myself skate on video for the first time around the age of twelve or thirteen. Besides being inadequate attire for subzero temperatures, skating dresses leave nowhere to hide. Repulsed by my own gangly image, I burst into tears. All arms and legs, my balance looked off, my head bobbing around on top of a tall, unsure frame. Every time I bent my knee it looked as though it was sharp enough to poke a hole through my tights.

While skating on a competitive synchronized skating team for many years, I had steered clear of being singled out and pulled aside by our coach to have the notorious talk about what I had been eating and how I looked in my skating dress, that I had seen other girls endure. They’d leave these conversations pink-cheeked, eyes downcast, sometimes pulling at their fleece sweatshirts. It didn’t matter that these were some of the strongest skaters on the team, the hidden workhorses holding up the weaker “pretty” girls placed strategically in more visible positions on the end of the lines.

In observing myself on video, I felt betrayed by my thinness and adherence to the rules that had gained praise. The result was not the image of beauty I thought I had attained. I was objectively too thin. Beauty as with “good health” are promoted as the acceptable goals of thinness, but potentially, they mask a different set of goals.

Skating taught me perseverance. By my mid-teens after gaining some curves through puberty, I felt more at home in my body. And after putting in many long hours at the rink, I felt and looked competent, even strong, as a skater. I passed all my gold level ice dances just in time for them to add the diamond series. I felt like Sisyphus on skates. For someone who just wanted to be done with skating already, I was pretty peeved.

Pudgy is cute, until it’s not

My sister began life as an adorable, pudgy baby who loved food. I was the picky eater who would stuff items from my plate into her mouth when no one was looking. I’d tap her foot under the table, and she’d turn towards me, mouth wide open to retrieve even broccoli florets from the prongs of my fork. The means to make my sister happy were definitely through her mouth, and those were the means often used to soothe her toddler cries. I remember being jealous of the attention she’d get as the cute one - her pudginess a key feature of her adorableness.

I’m not sure when it happened but eventually the pudge was no longer cute. By high school she was going with my mother to WeightWatchers meetings where they would weigh in weekly, without identifying the ratio of fat to muscle. I’m sure that a large portion of her weight was muscle mass, but this distinction was never made.

Let me be clear. I don’t blame any woman for having negative feelings towards her body especially her belly, feelings that translate to messaging that impacts her children and her grandchildren. I am subject to the same societal messaging, and I know how loud it gets. When my six-year-old son reached for the soft flesh around my belly button, I had a moment of reckoning in the form of a flinch. I asked him what he liked about it and he said “It’s soft and comfortable and it’s where I came from.”

Reclaiming Belly

I’ve done some work to reclaim the word “belly," to appreciate it’s softness and its coreness, the place that housed my babies and the home to my deepest feelings. I had help from two mentors. The way Rachel Yellin, a hypnobirthing coach, says the word “belly” makes it sound like a warm, protective blanket. For anyone having trouble sleeping, she has some free relaxation audio content on her website that I highly recommend. Andrea Ferretti, a brilliant meditation coach and lovely human, has a wonderful way of saying the word “belly” when she asks us to reconnect to our calm, compassionate center to regulate our nervous systems. The messaging of these mentors, that women’s bellies are essential grounding territory and deserve reverence for their innate emotional wisdom, is the important truth we must all fight to relearn and embrace.

The external war on women’s bellies, the ubiquitous messaging that they should be flat or invisible, permeates our minds until we confuse it as our own voice and connect it to our worth. Without the effort to reclaim our bellies, we are more susceptible to body dissatisfaction that can lead some of us down a path towards ineffective dieting and depressive symptoms and, for some, disordered eating. Besides the preoccupation and general miserableness caused by disordered eating, it can also contribute to worsening bone loss, a serious threat in mid to late life.

This conclusion from Exacting Beauty still rings true over twenty years later:

Finally, individual interventions alone will never fully be successful as long as society, as a whole, continues to accept an unhealthy, emaciated image as its ideal. Social activism may be necessary to truly prevent the majority of young girls from growing up hating their bodies and appearances. p 120

Thindoctrination

Watch any awards show on TV and you’ll see how much more work we need to do for women to place their value in more than appearing youthful and thin. The phenomenon of hugely popular pro-anorexia websites and social media influencers who promote “thinspiration” frightens and angers me. I’ve often talked about how language can help or hurt women in our fight for understanding ourselves and our health. After my hard-fought (and on-going) reclaiming of the word “belly,” I felt great ire resonating from deep within that sacred center when I first heard the meno-term that is by far my least favourite. Stay tuned…